Digital Panel Meters: A Comprehensive Guide to Modern Industrial Measurement

When a chemical reactor starts overheating, when a manufacturing line draws too much current, or when a storage tank approaches critical levels, operators need to know immediately. In modern industrial facilities, laboratories, and process control environments, that real-time awareness comes from digital panel meters mounted directly into control panels, where they continuously monitor voltage, temperature, pressure, flow, and dozens of other critical parameters that determine whether operations run safely and efficiently.

These compact, unassuming devices have largely replaced their analog predecessors over the past three decades, offering superior accuracy and capabilities that go far beyond simple measurement display. Digital panel meters have become the workhorses of industrial monitoring, combining precision measurement with practical features like alarm outputs, data communication, and process control capabilities, all packaged in a standardized, panel-mountable format that fits seamlessly into existing infrastructure.

Understanding how digital panel meters work, what they can do, and how to select the right one for your application helps you make informed decisions that can improve measurement accuracy, enhance process control, and potentially prevent costly equipment failures or safety incidents. This guide provides a comprehensive look at digital panel meters, from basic principles to advanced features and real-world applications.

Understanding Digital Panel Meters

A digital panel meter is an electronic display device specifically engineered to mount flush into a control panel, instrument enclosure, or equipment dashboard. At its most fundamental level, it performs a deceptively simple task: it receives an electrical signal from a sensor or transducer, processes that signal through sophisticated internal circuitry, and displays the corresponding measurement value in clear, easy-to-read digits on its front panel.

The input signal is typically analog in nature, meaning it varies continuously rather than in discrete steps. This signal might be a voltage from a temperature sensor measuring conditions inside an industrial oven, a milliamp current signal from a pressure transmitter monitoring hydraulic systems, or microvolt-level readings from a strain gauge on a weighing scale used in precision manufacturing. Regardless of the source, the meter's job is to transform this electrical representation of a physical phenomenon into a numerical value that humans can read and understand.

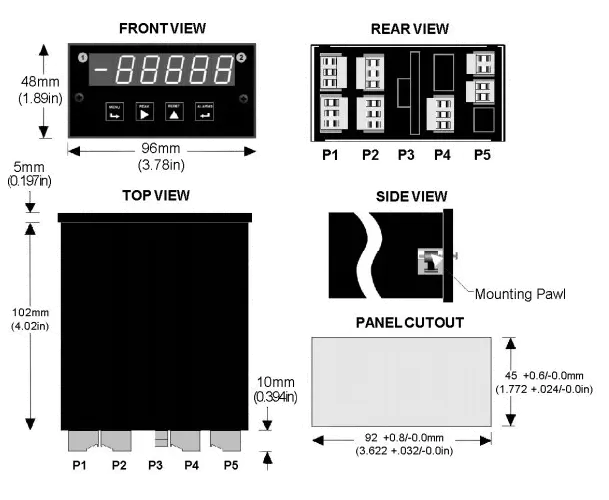

Figure 1: Typical 1/8 DIN digital panel meter showing standard mounting configuration.

Figure 1: Typical 1/8 DIN digital panel meter showing standard mounting configuration.

Internal Architecture and Signal Processing

Inside the compact housing of a digital panel meter lies a carefully orchestrated system of electronic components working in concert. The signal chain begins with the input terminals on the rear of the meter, where sensor wires connect. The incoming analog signal first encounters signal conditioning circuitry, which may include amplification for weak signals, attenuation for strong ones, filtering to remove electrical noise, and isolation to prevent ground loops that could corrupt measurements.

The conditioned signal then reaches the analog-to-digital converter, or ADC, which is arguably the most critical component in determining the meter's performance. The ADC samples the continuously varying analog signal at regular intervals and converts each sample into a digital number that the meter's microprocessor can work with. Modern digital panel meters typically employ high-resolution ADCs capable of 16-bit, 20-bit, or even 24-bit conversion, providing the precision necessary for demanding industrial applications.

The microprocessor serves as the meter's brain, performing several essential functions. It applies mathematical scaling to convert raw ADC values into engineering units, implements linearization algorithms to compensate for nonlinear sensor responses, manages the display to show the processed reading, monitors alarm conditions and controls outputs, and handles communication with external devices when equipped with appropriate interface boards.

The display itself, whether LED or LCD technology, presents the final reading to the operator. Most industrial digital panel meters use bright LED displays with digit heights of 0.56 inches or larger for visibility at distances up to several meters. The display typically shows 4 to 6 digits, with some models offering additional indicators for units, alarm status, or operating modes.

Beyond Basic Display: Control and Automation Features

While displaying measurements is the primary function, most modern digital panel meters offer capabilities that extend into control and automation realms. Set point outputs, typically implemented as relay contacts or solid-state switches, allow the meter to trigger actions when measurements cross predefined thresholds. This enables simple automation scenarios: activating a cooling fan when temperature exceeds a safe limit, sounding an alarm when tank level drops too low, or shutting down equipment when voltage strays outside acceptable bounds.

Analog retransmission outputs provide a scaled analog signal, usually 4-20 mA or 0-10V, proportional to the displayed reading. This allows the meter to serve as both a local display and a signal conditioner that can feed PLCs, chart recorders, or other analog equipment. The retransmitted signal often includes isolation to prevent ground loops and maintain signal integrity over long cable runs.

Digital communication interfaces have become increasingly common and sophisticated. Serial ports supporting RS232 or RS485 allow individual meters or networks of meters to communicate with computers, SCADA systems, or data loggers. More advanced models include Ethernet or WiFi connectivity, enabling meters to join industrial networks directly and transmit data using standard protocols like Modbus TCP/IP. Some meters can even host simple web servers, allowing operators to view readings and configure parameters through a standard web browser without specialized software.

Applications Across Industries

Digital panel meters find applications wherever reliable, continuous measurement is essential to operations. The diversity of industries and specific use cases speaks to the versatility and adaptability of these instruments. Understanding common applications provides context for appreciating the features and specifications that matter in real-world deployments.

Manufacturing and Process Control

In manufacturing environments, digital panel meters monitor and control process variables that directly affect product quality and production efficiency. Chemical processing plants use them to track reaction temperatures, pressure vessels, and flow rates of reactants. A temperature deviation of just a few degrees might ruin a batch worth thousands of dollars, so accuracy and reliability are paramount. The meter not only displays the current reading but can trigger alarms or activate cooling systems to maintain tight process control.

Food and beverage production facilities rely on digital panel meters for temperature monitoring during pasteurization, pressure control in carbonation systems, and level measurement in storage tanks. These applications often require meters with specific certifications for hygiene and food safety. Metal fabrication shops use panel meters connected to load cells for precise force measurement during forming operations, ensuring parts meet dimensional tolerances. Plastic injection molding machines employ meters to monitor melt temperature and injection pressure, critical parameters that determine part quality and cycle time.

Power Generation and Distribution

The electrical power industry makes extensive use of digital panel meters for monitoring and protecting equipment. In power generation facilities, whether conventional thermal plants or renewable energy installations, meters track voltage, current, frequency, and power factors at numerous points throughout the system. Generator output monitoring, transformer load balancing, and bus voltage regulation all depend on accurate, real-time measurements.

Solar and wind power installations present unique measurement challenges. Solar array voltage can vary widely with illumination conditions, requiring meters with auto-ranging capabilities and fast update rates. Wind turbine monitoring systems use meters to track generator output, bearing temperatures, and tower vibration levels. Battery energy storage systems, increasingly common in both grid-scale and commercial installations, employ panel meters to monitor cell voltages, charge/discharge currents, and temperature across battery banks, helping prevent dangerous conditions and extend battery life.

Electrical distribution panels in commercial and industrial facilities use panel meters to provide continuous visibility into system loading. Facility managers can identify circuits approaching capacity, detect power quality issues like voltage sags or harmonics, and document energy consumption for billing verification or energy management programs. Some facilities install meters on individual pieces of equipment to track energy usage and identify opportunities for efficiency improvements.

Figure 2: High-visibility LED display with 6-digit resolution for precise readings.

Figure 2: High-visibility LED display with 6-digit resolution for precise readings.

Laboratory and Research Environments

Research laboratories and testing facilities demand the highest levels of measurement precision and data integrity. Environmental chambers for materials testing use digital panel meters to monitor and log temperature and humidity with accuracies better than 0.1% of reading. These meters often include data logging capabilities or serial output for automated data collection, eliminating manual recording errors and providing timestamped records for regulatory compliance.

Calibration laboratories use precision panel meters as secondary standards for verifying the accuracy of other instruments. These applications require exceptional stability, often with temperature-compensated circuits and annual recalibration traceable to national standards. Universities and research institutions employ panel meters in experimental setups ranging from physics experiments requiring microvolt-level measurements to engineering test stands monitoring loads, pressures, and flows in prototype equipment.

Healthcare and Medical Devices

Medical equipment manufacturers integrate panel meters into devices like patient monitoring systems, therapeutic equipment, and diagnostic instruments. While many modern medical devices use custom displays integrated into sophisticated user interfaces, panel meters still find roles in equipment requiring simple, reliable measurement displays. Sterilization equipment, medical refrigerators and freezers, laboratory centrifuges, and physical therapy devices all may incorporate panel meters for temperature, speed, force, or time measurements.

These medical applications impose stringent requirements beyond simple accuracy. Equipment must meet electrical safety standards like IEC 60601, electromagnetic compatibility requirements to prevent interference with other medical devices, and often specific certifications for use in patient care areas. Meters used in medical applications typically undergo rigorous testing and validation to ensure they perform reliably in critical situations.

Automotive and Transportation

The automotive industry uses digital panel meters in manufacturing, testing, and vehicle integration. Engine dynamometers measure torque, speed, and power output during development and quality control testing. Environmental chambers subject vehicles to temperature extremes while meters monitor conditions. Electric vehicle charging stations incorporate panel meters to display charging current, voltage, and accumulated energy delivered. Vehicle assembly plants use meters with strain gauge inputs for precise torque monitoring during automated assembly operations.

Railway systems, both freight and passenger, employ panel meters for monitoring traction motor currents, brake system pressures, and HVAC system performance. Marine applications include monitoring engine parameters, tank levels, and electrical system status on vessels from small craft to large commercial ships. Aviation ground support equipment uses panel meters for hydraulic pressure monitoring, electrical power quality verification, and fuel system management.

Display Technologies and Human Factors

The display is the human interface to the meter, and its characteristics significantly impact usability and effectiveness in different environments. Understanding the trade-offs between display technologies helps in selecting meters appropriate for specific viewing conditions and operator requirements.

LED Displays: Visibility and Brightness

Light-emitting diode displays remain the dominant technology for industrial panel meters, and for good reasons. LEDs are inherently bright, emitting their own light rather than relying on external illumination or backlighting. This makes them highly visible in dim lighting conditions, which is common in many industrial settings like manufacturing floors, power plants, and equipment rooms where ambient lighting may be reduced to minimize heat or conserve energy.

Modern LED displays offer a choice of colors, each with distinct advantages. Red LEDs, the traditional choice, provide excellent visibility and consume moderate power. They're easily read at distances up to 20 feet or more, making them suitable for meters mounted on elevated panels or in large control rooms. Green LEDs have gained popularity in recent years, offering even better visibility in some lighting conditions and appearing subjectively brighter to the human eye than red LEDs of equivalent power. Amber LEDs provide a warm, easy-to-read display that some operators prefer for extended viewing. Blue LEDs, while less common, can be useful for color-coding multiple meters in a panel to distinguish different measurement types or process areas.

The seven-segment LED format, where each digit is formed from seven individual LED segments, has become the standard for numerical displays. This format provides clear, unambiguous digits that are easily distinguished even when viewed at an angle or from a distance. Digit height is a critical specification: common sizes include 0.4 inches for compact applications, 0.56 inches for standard 1/8 DIN meters, and up to several inches for large-digit displays intended for viewing across a room.

LED displays do have limitations. They consume more power than LCD alternatives, which can be a consideration in battery-powered or solar-powered installations. The individual LEDs have finite lifetimes, typically rated at 100,000 hours of continuous operation, though in practice, modern LEDs often far exceed this specification. Brightness may decrease over many years of continuous use, though this degradation is usually gradual and uniform across all segments.

LCD Displays: Versatility and Efficiency

Liquid crystal displays offer different characteristics that make them preferable in certain applications. LCDs consume significantly less power than LEDs, making them the obvious choice for battery-powered portable meters or solar-powered remote monitoring applications where power consumption directly impacts battery life or system cost. A typical LCD panel meter might draw one-tenth the power of an equivalent LED model.

LCDs also offer greater flexibility in what they can display. While seven-segment numeric displays are common, LCDs can easily incorporate alphanumeric characters for showing units, channel labels, or status messages. Graphic LCD displays can show bar graphs, trend plots, or even custom symbols and icons. This versatility makes LCD meters attractive for applications requiring more complex information presentation than simple numerical values.

The main drawback of LCDs is visibility. Unlike LEDs, LCDs don't emit light; they modulate transmitted or reflected light. In dim environments, LCDs become difficult or impossible to read without backlighting. While many LCD meters include LED backlights to address this issue, the backlight adds power consumption and somewhat negates the LCD's power advantage. Additionally, LCDs can be affected by extreme temperatures, with response times slowing at low temperatures and potential damage at very high temperatures, limiting their use in some industrial environments.

Resolution and Display Format

Display resolution, expressed in digits, determines how finely a meter can resolve measurements. A basic 3.5-digit display can show values from 0000 to 1999, useful for simple applications but limiting for applications requiring fine resolution. Four-digit displays (0000–9999) are common in general-purpose industrial meters. High-precision applications often demand 4.5 digits (00000–19999), 5 digits (00000–99999), or even 6 digits (000000–999999).

It's important to understand that display resolution doesn't automatically equate to measurement accuracy. A 6-digit display can show a reading of 123.456, but if the meter's internal accuracy is only ±0.1% of reading, the last digit or two are essentially noise and don't represent meaningful information. Reputable meter manufacturers match display resolution to the instrument's actual measurement capability, but some low-cost meters may provide excessive display resolution that creates a false impression of precision.

The decimal point position is typically programmable, allowing the same meter to display whole numbers or values with one, two, or more decimal places as appropriate for the application. This flexibility means a single meter model can serve applications as diverse as displaying 0–100.00 PSI from a pressure transducer, 0–1000 RPM from a tachometer, or 0.000–9.999 VDC for precision voltage measurement.

Figure 3: Proper panel installation ensures secure mounting and environmental protection.

Figure 3: Proper panel installation ensures secure mounting and environmental protection.

Signal Types and Input Compatibility

Matching the meter to your signal source is absolutely critical for successful implementation. Digital panel meters are designed to accept specific types of electrical signals, and selecting a meter compatible with your sensor or transducer output is the first and most important step in the specification process.

DC Voltage and Current

DC voltage inputs are among the most common and versatile. Meters may accept ranges from millivolts to hundreds of volts, with different models optimized for different spans. Low-voltage DC meters, with ranges like 0–200 mV or 0–2000 mV, connect directly to low-level sensors, while high-voltage models with ranges up to 600 VDC or more can monitor battery banks, solar arrays, or industrial DC power systems. Many meters offer multiple selectable ranges, either through jumper settings or software configuration, providing flexibility to work with various voltage levels without requiring external scaling resistors.

DC current meters measure current flow directly through the meter, typically in ranges from microamps to several amps. For higher currents, external current shunts provide a low-resistance path for current to flow, generating a proportional voltage drop that the meter measures. A common configuration uses a 50 mV shunt: at full-scale current, the shunt drops exactly 50 millivolts, which the meter reads on its millivolt range. This approach allows measurement of currents from tens of amps to thousands of amps with a standard meter.

AC Voltage and Current

AC measurements introduce additional complexity because the signal varies with time. True RMS meters provide the most accurate measurement, calculating the root-mean-square value of the waveform, which correctly represents the heating power of the signal regardless of waveform shape. This matters when measuring non-sinusoidal waveforms common in modern electrical systems with electronic loads and switching power supplies. Cheaper average-responding meters measure the average value and scale it to read correctly for sine waves, but they can show significant errors with distorted waveforms.

AC current measurement typically employs current transformers rather than shunts. A CT encircles the conductor carrying the current to be measured and produces a secondary current, typically 5 amps or 1 amp at full scale, proportional to the primary current. The meter connects to the CT secondary through appropriate burden resistors, measuring the resulting voltage. This method provides isolation between the high-current circuit and the meter, an important safety feature when monitoring high-voltage AC systems.

Process Signals: 4-20 mA and 0-10V

The process control industry has standardized on 4-20 milliamp current loops for transmitting measurement signals over distance. This ubiquitous signal format has several advantages: the 4 mA minimum (representing zero measurement) allows the receiving device to distinguish between a zero reading and a broken wire, current signals are largely immune to voltage drop in long cable runs, and they're less susceptible to electrical noise than voltage signals. A transmitter monitoring tank level, for example, outputs 4 mA when empty, 12 mA at half full, and 20 mA when completely full.

Panel meters for process signals accept the 4-20 mA input and scale the display to show engineering units. The meter's software allows programming the display to read 0–100% directly, or to any desired span like 0–1000 gallons for a tank level application. The meter may also provide excitation voltage to power 2-wire transmitters, simplifying wiring by allowing the meter itself to supply power to the remote transmitter through the same two wires carrying the signal.

Voltage process signals, typically 0–10 VDC or 0–5 VDC, serve similar purposes in applications where voltage transmission is preferred. Some industrial control systems, PLCs, and data acquisition systems output voltage signals, and meters accepting these inputs connect directly without requiring additional interface hardware. Like current process meters, voltage process meters provide user scaling to display in appropriate engineering units.

Temperature Sensors: Thermocouples, RTDs, and Thermistors

Temperature measurement presents unique challenges because temperature sensors produce signals that vary in complex, often nonlinear ways with temperature. Digital panel meters designed for temperature inputs include specialized signal conditioning and mathematical linearization to handle these sensors directly, eliminating the need for external transmitters in many applications.

Thermocouples generate small voltages, typically tens of microvolts per degree, through the Seebeck effect when junctions of dissimilar metals are at different temperatures. Different thermocouple types (J, K, T, E, R, S, B, N) use different metal combinations and have different voltage-versus-temperature relationships. A meter designed for thermocouples must know which type is connected and apply the appropriate nonlinear conversion to display temperature correctly. Premium thermocouple meters include automatic cold junction compensation, measuring the temperature at the meter's input terminals and mathematically correcting for it to provide accurate readings without requiring an ice bath reference.

Resistance temperature detectors, or RTDs, change resistance predictably with temperature. Platinum RTDs, particularly the Pt100 with 100 ohms resistance at 0°C, have become industry standards for accurate temperature measurement. The meter applies a small, precise excitation current through the RTD and measures the resulting voltage, calculating resistance and then temperature. RTDs can connect via 2-wire, 3-wire, or 4-wire configurations, with 3-wire and 4-wire hookups compensating for resistance in the connecting wires to maintain accuracy over long cable runs.

Thermistors, particularly NTC (negative temperature coefficient) types, exhibit large resistance changes with temperature, making them useful for applications requiring high sensitivity or narrow temperature ranges. Their highly nonlinear response requires sophisticated curve-fitting in the meter, but modern digital panel meters can store custom thermistor curves to provide accurate temperature display.

Strain Gauges and Load Cells

Load cells and strain gauges produce extremely small signals, typically millivolts full scale, requiring meters with high sensitivity and low noise. These sensors are essentially Wheatstone bridges that unbalance slightly when subjected to mechanical strain. A typical load cell with 2 mV/V sensitivity, when excited with 10 volts, produces only 20 millivolts at full-scale load.

Meters for these applications offer excitation voltage outputs to power the bridge, typically 5V or 10V, and high-resolution inputs capable of resolving single microvolts. They may provide 4-wire or 6-wire connection options to eliminate errors from resistance in excitation and sense leads. Advanced features like ratiometric operation automatically compensate for variations in excitation voltage, improving accuracy and stability. Software in the meter handles scaling from millivolts to engineering units like pounds, kilograms, or newtons, and may include tare functions for zeroing out container weight or applying other offset corrections.

Accuracy, Precision, and Error Sources

Understanding measurement accuracy and the factors that affect it is essential for evaluating whether a particular meter will meet application requirements. Accuracy specifications can be confusing, and the real-world performance of a meter depends on many factors beyond the basic specification sheet numbers.

Reading Accuracy Specifications

Manufacturers typically specify accuracy as a percentage of reading plus a fixed number of counts. For example, a specification of ±0.02% of reading ±2 counts means the error has two components. The percentage term is proportional to the measured value: a reading of 10000 could be off by up to 2 (0.02% of 10000), while a reading of 1000 could be off by 0.2 (0.02% of 1000). The fixed count term adds a constant offset, so the total possible error on the 10000 reading is 2 + 2 = 4 counts, while the 1000 reading could be off by 0.2 + 2 = 2.2 counts.

This specification format reveals an important characteristic: accuracy is best at high readings and degrades toward the low end of the range. At very low readings, the fixed count error dominates. For a meter reading 100 with the same ±0.02% ±2 specification, the percentage error is only 0.02, but the fixed error is still 2 counts, making the total possible error 2.02 counts or about 2% of reading. This is why it's generally advisable to size measurement ranges so that typical readings fall in the upper half of the meter's span.

Some specifications use percentage of full scale instead of percentage of reading. A ±0.1% of full scale specification on a meter with 20000 full scale means the error can be up to 20 counts anywhere in the range. This is simpler to work with but generally less favorable than a percentage of reading specification except at very low readings.

Temperature Effects and Stability

Temperature affects every electronic component in a meter. Resistors, capacitors, voltage references, and semiconductors all change their characteristics with temperature, potentially shifting the meter's reading. High-quality meters incorporate temperature compensation through several techniques: using precision components with matched temperature coefficients, incorporating temperature sensors that feed compensation algorithms, and storing calibration coefficients at multiple temperatures for interpolation.

Manufacturers may specify accuracy over a reference temperature range, typically 23°C ±5°C, with reduced accuracy outside that range. Additional temperature coefficient specifications, expressed as parts per million per degree Celsius or as additional error per degree, indicate how much additional error to expect when operating at temperature extremes. In applications where ambient temperature varies widely, paying attention to temperature specifications and perhaps choosing a meter with superior temperature performance can be worthwhile.

Long-term drift, the gradual change in calibration over months or years, is another stability consideration. Even without temperature changes, component aging can cause small shifts in meter readings. Quality meters specify drift in terms of parts per million per year or as a percentage per year. For critical measurements, periodic recalibration, typically annually, ensures continued accuracy.

Noise, Filtering, and Update Rates

Electrical noise is endemic in industrial environments. Motor drives, relays, welders, and other equipment create electromagnetic interference that can couple into measurement circuits and corrupt readings. Digital panel meters employ several strategies to minimize noise effects. Input filtering, using capacitors and sometimes inductors, attenuates high-frequency noise before it reaches the ADC. Integration-type ADCs, which average the input over a period of time rather than sampling instantaneously, provide inherent noise rejection, particularly for noise at the power line frequency.

Many meters offer selectable digital filtering, averaging multiple readings to smooth out noise at the expense of response speed. A heavily filtered meter might average 10 or 20 readings before updating the display, providing stable readings in noisy environments but responding slowly to changes in the measured value. Unfiltered or lightly filtered operation gives fast response but may show jittery readings in noisy conditions. The appropriate filter setting depends on whether you need to see rapid changes or prefer stable, averaged values.

Update rate, the frequency at which the meter takes new readings and updates the display, varies from several times per second in basic meters to 50 or 60 conversions per second in high-speed models. Fast update rates enable peak and valley capture, catching transient events that might be missed with slower meters. They're also essential for control applications and real-time computer interfacing. However, faster update rates may require reducing the integration time, potentially reducing noise immunity unless sophisticated filtering algorithms are employed.

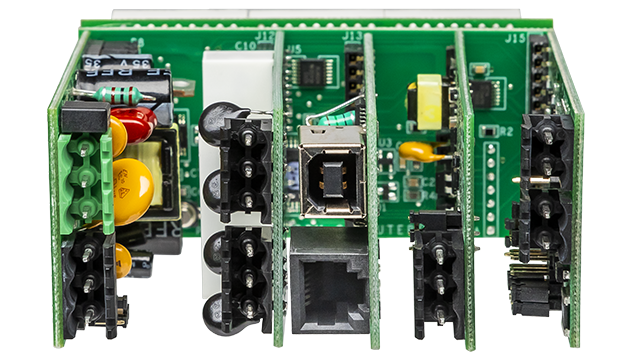

Figure 4: Modular options expand functionality with relays, analog outputs, and network connectivity.

Figure 4: Modular options expand functionality with relays, analog outputs, and network connectivity.

Advanced Features for Modern Applications

Beyond basic measurement and display, contemporary digital panel meters incorporate sophisticated features that address complex application requirements and integrate with modern control and data systems. Understanding these capabilities helps identify when a more advanced meter might provide significant value despite higher initial cost.

Linearization and Custom Curves

Many sensors produce outputs that aren't linear with the physical parameter being measured. Thermistors, for instance, have highly nonlinear resistance-versus-temperature curves. Some flow meters, level sensors, and other transducers similarly exhibit nonlinear responses. While you could use external linearizing circuitry or accept nonlinear display readings, many modern meters include programmable linearization that mathematically compensates for sensor nonlinearity.

For standard sensors like thermocouples and thermistors, the meter may have built-in curves. For custom sensors, the meter might allow programming a multi-segment curve, essentially a lookup table that maps input values to output readings. You program multiple input/output pairs, and the meter interpolates between them. This allows accurate display from virtually any sensor, regardless of how nonlinear its response might be.

Peak, Valley, and Statistical Functions

High-speed meters can capture and hold maximum and minimum values, automatically tracking peak and valley readings over time. This proves valuable in applications where transient events matter. Motor starting current, pressure spikes in hydraulic systems, temperature excursions during thermal cycling — all these phenomena might be missed if you're only watching the current reading. Peak/valley capture ensures these events are recorded for later review.

Some meters extend this concept to maintain running statistics: average values over selectable time periods, standard deviation to quantify process variability, or even histograms showing the distribution of readings. These features transform the meter from a simple display into a data analysis tool that can provide insights into process behavior and help identify issues before they become serious problems.

Rate of Change and Derived Measurements

The rate at which a measurement changes can be as important as its absolute value. Temperature rise rate during heating processes, pressure change rate when filling tanks, or flow acceleration in pipelines all provide useful process information. Meters with rate-of-change capabilities calculate and display the time derivative of the input, showing units per second, per minute, or per hour as configured.

Totalizing functions integrate the input over time, accumulating a running total. This turns a flow rate meter into a totalizer showing accumulated volume, or allows an energy meter to track total kilowatt-hours consumed. Reset functions might clear the total on command, or the meter might maintain both a resettable total and a grand total that can't be reset. This proves essential in applications like batch processing where you need to measure quantities per batch while also tracking overall production.

Multi-Channel and Scanning Operation

Some applications require monitoring multiple related measurements. Multi-channel meters accept inputs from several sensors and can display them sequentially, switching automatically at programmed intervals, or allow manual selection via front-panel buttons. This reduces panel space and cost compared to installing separate meters for each measurement point.

More sophisticated implementations might display multiple channels simultaneously on graphic LCD screens, or perform calculations across channels. For example, a dual-channel meter might display the difference between two temperature sensors, useful for monitoring differential temperature across a heat exchanger. Or it might display the ratio of two flow measurements, indicating mixture proportions in a blending process.

Data Logging and Trending

While traditional panel meters display current values, some models include internal memory to log measurements over time. The meter might store thousands of readings with timestamps, creating a data record that can be reviewed later or downloaded to a computer for analysis. This internal logging can be invaluable for troubleshooting intermittent problems, documenting process conditions for quality records, or demonstrating compliance with operating specifications.

Meters with graphic displays might show trend plots directly on the screen, giving operators visual feedback about recent history and helping them identify patterns or anomalies. This brings some of the benefits of chart recorders in a compact, purely electronic format without the ongoing cost of chart paper or ink.

Selecting the Right Digital Panel Meter

Choosing an appropriate digital panel meter requires balancing numerous technical requirements against practical considerations like cost, availability, and long-term support. A systematic approach helps ensure the selected meter will perform reliably throughout its service life.

Application Requirements Analysis

Start by clearly defining what you need to measure and why. What physical parameter are you monitoring? What type of sensor or transducer provides the signal? What's the expected range of measurements, and what accuracy do you actually need? It's tempting to default to the highest accuracy available, but precision instruments cost more and may require more careful installation and maintenance. Match the meter's capabilities to genuine requirements.

Consider the application environment. Will the meter be exposed to temperature extremes, humidity, vibration, or corrosive atmospheres? Industrial environments often demand rugged meters with appropriate environmental ratings. A meter destined for a climate-controlled control room has different requirements than one mounted on outdoor equipment or in a harsh chemical processing area. IP65 or NEMA 4X ratings from the front panel protect against dust and water when panel-mounted, extending meter life in demanding conditions.

Think about the human factors. Who will be viewing the meter, from what distance, and under what lighting conditions? Larger digits and brighter displays cost more but might be essential for visibility. Will operators need to interact with the meter, perhaps adjusting setpoints or acknowledging alarms? Front-panel accessibility and intuitive user interface become important considerations for meters that require regular operator interaction.

Control and Communication Needs

Determine whether simple display is sufficient or if you need control outputs and communication capabilities. If the meter needs to trigger alarms or control equipment, you'll require relay outputs or analog retransmission. Count the number of setpoints needed and their functions — simple high/low alarms, latching alarms, control relays that cycle equipment on and off, or more complex logic.

For data communication, consider both current needs and future expansion. Even if you don't initially plan to network meters, adding communication capability at installation is far cheaper than retrofitting later. RS485 serial communication provides a cost-effective way to network many meters to a central monitoring point. Ethernet connectivity offers easier integration with modern IT infrastructure and SCADA systems. Wireless options eliminate cabling in retrofit applications or locations where running wires is impractical, though they introduce complexity around power and network security.

Installation and Mounting Considerations

Physical compatibility with existing panels is essential. Most industrial digital panel meters conform to 1/8 DIN dimensions, with a panel cutout of approximately 92mm × 45mm and a faceplate that overlaps the cutout to provide environmental sealing. Verify not just the cutout size but also the depth behind the panel — meters vary in how far they protrude, and deep meters might not fit in shallow enclosures or might interfere with other equipment mounted behind the panel.

Wiring access and connector types matter in tight spaces. Some meters use screw terminals directly on the rear, requiring sufficient room to manipulate a screwdriver during installation and making field wiring somewhat tedious. Others employ plug-in terminal blocks that can be removed for wiring at a workbench, then plugged back into the meter for faster installation. This modular approach greatly simplifies installation and maintenance, particularly when replacing failed meters or performing panel modifications.

Power Supply Compatibility

Confirm that available power matches the meter's requirements. Many modern meters accept universal power supplies, typically 85–264 VAC or optionally 10–48 VDC, making them adaptable to various installations without ordering special variants. This flexibility is particularly valuable in international applications where line voltage varies, or in systems that might switch from AC to DC backup power.

In battery-powered or solar-powered systems, power consumption becomes critical. An LED meter drawing several watts might require significantly larger batteries or solar panels compared to an LCD meter drawing only milliwatts. Calculate total system power budget carefully, including the meter, any powered sensors, and communication equipment, to ensure reliable operation throughout the expected service interval.

Vendor Selection and Support

Choosing Laurel Electronics as your panel meter supplier pays dividends over the life of your installation. With decades in the business and a reputation for standing behind our products, Laurel Electronics provides the kind of responsive, knowledgeable application engineering support that helps you troubleshoot installation issues and select the right configurations — the level of technical partnership that many other manufacturers simply don't offer.

Documentation quality indicates how seriously the manufacturer takes customer success. Comprehensive manuals with clear wiring diagrams, setup instructions, and troubleshooting guides make installation and commissioning much easier. Look for manufacturers who publish full specifications, application notes, and perhaps even setup software that simplifies configuration. The best manufacturers offer calibration services and stock spare parts, ensuring you can maintain meters throughout their service life rather than replacing them when they drift out of calibration or suffer component failures.

Total Cost of Ownership

While initial purchase price is easy to compare, total cost of ownership encompasses installation labor, ongoing maintenance, calibration services, and potential replacement costs. A meter that's quick to install and configure saves labor costs that might offset a higher purchase price. Features like plug-in terminal blocks or auto-configuration reduce commissioning time. Meters requiring frequent recalibration or having high failure rates increase lifetime costs through maintenance labor and downtime.

Consider standardization across your facility. Using the same meter model for multiple applications simplifies spare parts inventory, reduces training requirements, and makes troubleshooting more efficient because technicians become familiar with one platform rather than learning multiple different meters. While it might be tempting to optimize each application individually, the operational advantages of standardization often outweigh the potential savings from selecting the cheapest suitable meter for each specific application.

Installation Best Practices

Proper installation significantly impacts meter performance and reliability. Following best practices during installation prevents problems and ensures measurements remain accurate throughout the meter's service life.

Panel Mounting and Environmental Sealing

Cut the panel opening to the manufacturer's specified dimensions, ensuring corners are square and edges are smooth to allow proper sealing. Most 1/8 DIN meters include a gasket that seats between the meter bezel and the panel, providing environmental sealing when the meter is secured with its mounting bracket. Tighten the mounting bracket evenly to compress the gasket uniformly without over-stressing the meter case.

Ensure adequate clearance behind the panel for the meter body, wiring, and any plug-in modules. Allow extra space for cable bending radius — forcing wires into tight bends can damage insulation and eventually lead to failures. In dense panels with many instruments, plan the layout to maintain minimum clearances and allow access for future maintenance or meter replacement.

Signal Wiring and Grounding

Route signal wiring separately from power wiring, particularly high-current or switching power circuits that can induce noise. Use shielded or twisted-pair cable for low-level signals like thermocouples, RTDs, or strain gauge inputs. Connect shield to ground at one end only, typically at the meter, to avoid ground loops that can introduce errors or instability.

Pay careful attention to grounding, particularly in systems with multiple instruments or long cable runs. Isolated meters, where the input circuitry is electrically isolated from power and chassis grounds, help prevent ground loop issues, but proper grounding practices are still essential. Establish a clean earth ground point and connect meter chassis grounds to this point with heavy-gauge wire. Avoid daisy-chaining grounds from one meter to another, as this can create ground potential differences that affect measurements.

Configuration and Calibration

After physical installation, configure the meter for your specific application. This typically involves setting the input type and range, programming display scaling, configuring alarm setpoints if applicable, and enabling any communication parameters. Many meters offer both front-panel programming and computer-based setup software. Front-panel programming works for simple applications, but software-based configuration is faster and less error-prone for complex setups or when configuring multiple identical meters.

Verify calibration after installation using known reference standards appropriate for your measurement type. For voltage meters, use a precision voltage source or calibrated multimeter. For temperature meters, use a temperature calibrator or stable temperature bath. Compare the meter reading to the known reference and adjust calibration if necessary, following the manufacturer's procedures. Document the as-found and as-left calibration results for quality records and future reference.

The Future of Digital Panel Meters

Digital panel meters continue to evolve, incorporating new technologies and capabilities that extend their utility in modern industrial and laboratory environments. Several trends are shaping the next generation of these essential instruments.

Connectivity and Industry 4.0

The push toward Industry 4.0 and the Industrial Internet of Things is transforming traditional panel meters into connected sensors that participate in broader data ecosystems. Modern meters with Ethernet, WiFi, or cellular connectivity can publish data directly to cloud platforms, feed enterprise databases, or integrate with analytics systems without requiring dedicated data acquisition hardware.

Standardized protocols like MQTT, OPC-UA, and RESTful APIs make it easier to integrate meters into diverse systems. Web-based configuration interfaces eliminate the need for proprietary software, allowing setup and monitoring through standard browsers on any device. This democratization of access means plant managers can check critical measurements from their smartphones, maintenance personnel can troubleshoot remotely, and data scientists can access historical trends for analysis without needing physical access to equipment.

Enhanced Intelligence and Diagnostics

Meters are becoming smarter, incorporating local processing power that was unthinkable in early digital designs. Advanced signal processing algorithms can automatically detect and compensate for sensor degradation, identify electrical interference patterns, or recognize measurement anomalies that might indicate developing equipment problems. Some meters now include onboard diagnostic capabilities that monitor their own health, flagging calibration drift or component issues before they lead to measurement errors.

Machine learning algorithms, running either locally or in connected cloud services, can learn normal patterns in measurement data and alert operators to deviations that might indicate process upsets or equipment malfunctions. This predictive maintenance capability transforms meters from passive measurement devices into active participants in maintaining system reliability.

Integration with Digital Twins

Digital twin technology, which creates virtual replicas of physical systems, relies on real-time data from instruments like panel meters. As digital twin adoption grows, meters that can seamlessly integrate with these systems become more valuable. The meter becomes not just a display for operators but also a data source feeding sophisticated simulation and optimization models that help predict equipment behavior and optimize operating parameters.

Conclusion: Making Informed Choices

Digital panel meters have evolved from simple numeric displays into sophisticated measurement and control instruments that form essential links in modern industrial systems. Understanding their capabilities, limitations, and proper application enables you to select and deploy meters that provide reliable, accurate measurements throughout their service lives.

The best meter for any given application balances multiple factors: measurement accuracy matched to actual requirements, display format and size appropriate for viewing conditions, environmental protection suitable for the installation location, input compatibility with available sensors, communication and control features aligned with system architecture, and total cost of ownership that accounts for installation, maintenance, and long-term support.

Whether you're monitoring a single parameter in a simple application or implementing a comprehensive measurement system across a facility, digital panel meters offer proven, cost-effective solutions. Take time to clearly define your requirements, evaluate options thoroughly, and follow best practices in installation and commissioning. The result will be a measurement system that serves reliably for years, providing the accurate, timely information necessary for effective process control, quality assurance, and operational efficiency.

As technology continues advancing, digital panel meters will incorporate new capabilities while maintaining the fundamental advantages that have made them industrial workhorses: compact size, straightforward installation, clear displays, and reliable performance. Understanding both current capabilities and emerging trends helps you make decisions that will serve well not just today but throughout the expected service life of your instrumentation.